|

Capital Rambles:

|

Mer Bleue

Human history

East of Ottawa lies almost 5,000 acres of peat bog with the mysterious name of "Mer Bleue" which, in English, means "Blue Sea." How did this fascinating spot get its name?

During the early days of homesteading east of Ottawa, when weather conditions were right, swirling mist obscured the vast wetlands. Local residents called the area "Mer Bleue," and the name stuck. Today Mer Bleue is a wildlife sanctuary and conservation area managed by the National Capital Commission (NCC).

One of the first buildings erected near Mer Bleue was an 1845 square timber homestead. George Gray, formerly of New Edinburgh (the village built in Bytown by Thomas MacKay for his millworkers), built his residence on Borthwick Ridge, where he owned and operated a 200-acre farm with his two sons, John and Allan. The Grays were by no means alone on the ridge, which recalls the name of another early settler, Thomas Borthwick. The Borthwicks were quite prominent here and recognized the value of the natural spring water that was so abundant here. They founded the Borthwick Mineral Spring, and began to bottle the natural product, which they sold in Ottawa.

As mentioned, water defines the NCR — and it's not just potable water or rivers that I'm thinking about. Just as much as we enjoy spas these days, in the late 1800s in Canada, sulphur baths and "taking the waters" was considered healthful and trendy. After all, on 25 November 1895, Banff National Park was created as Canada's first national park, largely because of the Cave and Basin, a natural sulphur spring. In Europe, spas had been associated with natural healing for years and their touristic value was well known in places such as Germany and Hungary. Here in the capital area, we are blessed with many potable springs, and yet the legacy of the saline Champlain Sea has also left us with valuable "sulphur waters," too. Carlsbad Springs is one such former site, located southeast of Mer Bleue. In days gone by, it was a popular spa where Ottawans and others came to "take the baths." Lesser-known Victoria Sulphur Springs was located further north, near Green's Creek. Just like its neighbour, it was known for its hotel, which was owned by the Lafleur family, where in 1887 guests paid $5.00 for a dozen tickets to enjoy the baths.

|

|

It is not surprising that water was such a desirable, and hence valuable, economic commodity in the area. Cholera and typhoid were all-too-common diseases well into the early 1900s. Ottawans suffered significant typhoid epidemics in 1911 and 1912. No wonder then, back in the late 1800s, that clear and pure spring water provided full employment for the Borthwick family.

Descendents of yet another pioneering family who homesteaded on this ridge — the McCartneys' — are still there. Their white trucks decorated with a cartoon chicken can be seen throughout the city, delivering poultry meat to various locations. Here on the ridge, you pass their farm when you near the Mer Bleue boardwalk trail. Some 3 km north of Borthwick Ridge lies a parallel ridge that takes its name from John Dolman, a Justice of the Peace and health inspector who settled here between 1880 and 1890.

So far, I've talked about human history "around" the bog. But who is associated with Mer Bleue bog itself? In 1919, a high school teacher named James Collins, who lived in the nearby village of Russell, penned an unpublished manuscript entitled The Chronicle of Carlsbad Springs. Author and late NCC historian Courtney J. Bond excerpted several paragraphs of it in his now out-of-print classic guide and history, The Ottawa Country. Collins evocatively describes the Mer Bleue area while on a canoe trip along Bear Creek to Ottawa:

The sun was setting behind the forest of spruce and tamarack in the Mer Bleue. On the edge of the clearing was the large potash-kettle supported by huge boulders from which the grey smoke of the smouldering elm and ash logs rose slowly skyward. A smudge burned before the door of MacDonald's shanty to chase the mosquitoes, painfully troublesome about the Forks at that time. The voice of the cuckoo sounded far above the trees towards the meadows. The oriole piped sweetly in the neighbouring woods…

The next morning was perfect. The mist hung over the bank and the clearing. A few of the whip-poor-wills were still singing. The smoke from the potash fire smelled crisp and invigorating as it rose from the still smouldering embers. … The cock flew up on the fence near the old stable and gave one last crow before he started his day's roaming with his flock. The breakfast being over, Angus MacDonald is seen down by the brook putting the last finishing touches on the cargo of potash and adding anything else he may have had of marketable value. His wife is now seated in the canoe in the place prepared for her. MacDonald goes back to the shack and brings something out laying it carefully near where he shall sit and row. It is his old trusty musket which perhaps saw service in the Glengarry Light Infantry.

This last military note calls to mind another human "use" of Mer Bleue. Ten years after Collins wrote his memoirs, the Great Depression was in full swing. Just as in what is now Gatineau Park, where at least one trail (Skyline) was built by unemployed men as a make-work project, a similar scheme happened here. Workers dug ditches at the east end of the bog but fortunately, they did not succeed in draining it. Sometime later, during WW II, the Royal Canadian Air Force used the "worthless" bog as a practice bombing range.

Today, Mer Bleue is a treasured gem of the NCC's Greenbelt system of parklands — itself a legacy of Jacques Gréber's 1950 master plan of the capital. Thankfully, wetland systems are recognized as precious ecological habitats that need protection from human intervention and development. Enter the international body responsible for their preservation, the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance. As part of our unfolding human history, Mer Bleue is now a preserved wetland under the 1971 Convention on Wetlands signed in Ramsar, Iran. This intergovernmental treaty identified wetlands and their resources and today there are 136 contracting parties to the convention, with 1,267 protected wetland sites throughout the world totalling 107.5 million hectares.

Natural history

Mer Bleue's almost 3,300-hectare wetland represents a throwback to the eras of the Laurentide Ice Sheet and the Champlain Sea. Over 9,000 years ago a southern branch of the Ottawa River coursed through here. If the Parliament Buildings had existed during that great sea, they would have been submerged in saline water where whales and seals swam. Dolman and Borthwick ridges were islands, large sand and gravel "bars" created as ice withdrew. Approximately 8,000 years ago, the southern branch of the estuary disappeared, replaced by a wetland created by underlying clay that prevented water from escaping. Cattails grew in the algae-rich waters. Meanwhile, just north of the Mer Bleue wetland, the channel of the Ottawa River watershed was narrowing as the land rebounded from the weight of the ice sheet.

Snapping turtle at Mer Bleue. Photo Eric Fletcher October 2003. |

Today's Mer Bleue bog lies north of Bear Brook and Carlsbad Springs, two other vestiges from the ice age. Vegetation in the bog includes deposits of sphagnum peat moss forming a dense mat up to 6 m deep. Although the sphagnum moss on Mer Bleue's surface looks dense, as if it would hold your weight, it won't, and this is why bogs are particularly treacherous. The moss mats fulfill a significant ecological function, helping the wetland serve as "lungs" of the earth, much in the same way as mangrove trees do in the tropics. Mer Bleue bog is critical to the health of its surrounding landscape because it filters contaminants from the watershed region. It also serves as natural reservoir by replenishing the water table. More than 75 percent of Ontario's wetlands have been drained, so it is particularly important that the NCC remains committed to maintaining Mer Bleue as an internationally significant conservation area.

Nevertheless, there is more to life at Mer Bleue than sphagnum moss. Dramatic dark green spires of black spruce trees grow here, as well. Come autumn, the green needle-like leaves of the deciduous conifer, the tamarack (or larch), turn brilliant gold before dropping to the mossy mat. Carnivorous plants are also visible; look for the pitcher plant and sundew. Other plants typical of northern boreal forest ecological zones exist here, including leatherleaf, bog cranberry, and bog laurel. Another feature of Mer Bleue is a series of islands inside the bog, where birch and aspen grow.

Mer Bleue also features a "lagg," a term referring to the moat of water surrounding the bog. The lagg was created by beavers that, doing what comes naturally, dammed all the outflows of the bog. Mer Bleue's lagg is becoming increasingly choked by cattails. Here you will surely hear that harbinger of spring, the red-winged blackbird. Also listen for the comical-sounding, "gurgling water" call of the well-camouflaged American bittern.

Beavers at work! Photo: Eric Fletcher 2002 October. |

While strolling along the Mer Bleue boardwalk, you will see evidence of beavers and their rodent relatives, muskrats, whose "swimming channels" cut narrow swathes through the cattails encroaching the bog. Look also for muddy "preening tufts" where black, mallard, and other ducks stand to clean themselves. Tell-tale feathers floating on the water's surface reveal these areas to you, even if their former owners have flown off at your approach.

Mer Bleue is home to many unusual birds. The boardwalk offers birdwatchers a rich variety of species, as does an amble along the ridge. Nashville warblers; northern shrike; black-backed woodpecker; northern mockingbirds; several unusual sparrows: Lincoln, clay-coloured, and Henslow’s; sedge wren; olive-sided flycatcher; and orchard oriole have all been reliably identified in Mer Bleue, according to area birders Larry Neily and Tony Beck.

Amateur zoologists among you will delight to realize that Mer Bleue is also home to some creatures that are extremely rare throughout North America, if not the world. One such critter is the spotted turtle. With its black carapace and bright yellow or orange spots, this small amphibian (127 mm shell length) is easily recognized — if you are so fortunate as to spot it. If you have ever tried to approach wild turtles, however, you already know that even your softest footsteps (or paddle strokes) warn them of your presence from many metres away. Frustratingly, these truly wild creatures tend to slip into the water well before you can get close enough to observe them. (That's another good reason to bring binoculars along on your ramble.)

Hopefully Mer Bleue will survive for many more thousands of years despite inevitable urban sprawl. Other factors threaten the bog. For example, while we attempt to prevent destructive wild fires we have to recognize that we are impeding the natural evolution of landscape. Without such checks and balances, and with the ever-constant unchecked activity of beavers, the vegetation of Mer Bleue is becoming less diverse.

Before you go on the Ramble

Why go? Mer Bleue is a rare example of a sphagnum bog wetland system. Boardwalk and other trails permit you to get "up close and personal" to an otherwise impenetrable, rare ecosystem.

Distances: Mer Bleue is roughly a 20 km drive from Parliament Hill. The Boardwalk Trail is a gentle 1.2 km walk

Modes of exploration: You can cycle to the bog but note that bikes are not permitted on the boardwalk itself. In winter there are cross-country ski trails here but again, stay on trails to conserve the bog habitat and biodiversity.

The Ramble: Highway 417 east to Walkley Road, Baseline Road, Ridge Road and Mer Bleue Boardwalk Trail.

Parking: parking lot on-site.

Facilities: There are washrooms (outhouses) at the trailhead. The path and boardwalk are wheelchair friendly, but remember: in inclement weather you are totally exposed. If you are in a wheelchair you must be very well prepared as there is no shelter from wind, sun, or rain. As you might expect, insects like black flies and mosquitoes are fierce here in season (mid-May through July, minimum). Pack bug repellent and wear wide-brimmed sunhats for both bugs and sun.

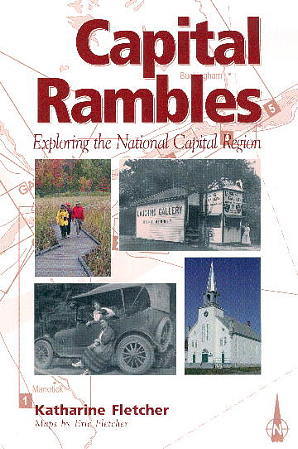

This is only the introduction to one of 12 fascinating places to explore around the National Capital Region.

Other rambles include: Rideau Canal (from downtown Ottawa to Manotick), Pettie Island, Cumberland Village, Lievre River to Poltimore, Gatineau River to Wakefield, Hull's Brewery Creek Paddle and Bicycle, Aylmer Road, Gatineau Park Circuit, Ottawa River Loop, Chats Falls (Quyon) Canoe Trip, and Mississippi Mills.